In his 2013 novel Inferno, Dan Brown mentions the struggle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines.

As it was so important for both Medieval Florence and the life of poet Dante Alighieri, we want to briefly explain what this opposition was about.

Simply put, the Guelphs and Ghibellines were rival parties in medieval Germany and Italy that supported the papal party and the Holy Roman emperors respectively. But in Italy, the divisions became more a function of rivalries between cities and even local families.

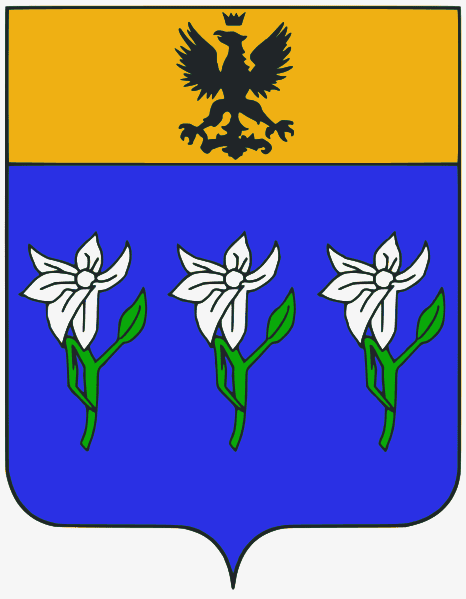

Coat of arms of an Italian family with Ghibelline-style heraldic chief at top

Origins

The designations Guelphs and Ghibellines originated in the 12th century from the names of rival German houses in their struggle for the title of Holy Roman Emperor. The election of Lothair II (c. 1070–1137), German king from 1125 and Holy Roman emperor from 1133, was favored by the pope and opposed by the Hohenstaufen family of princes.

This was the start of the feud between the house of Welf (Guelph), the followers of the dukes of Saxony and Bavaria, and the house of the lords of Hohenstaufen, whose castle at Waiblingen (near present-day Stuttgart) lent the Ghibellines their name.

Eventually, the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict gave way to a civil war that was finally settled in 1152 by the election of Frederick I (Barbarossa), the son of a Hohenstaufen father and a Welf mother (When Henry the Lion, a Welf, incurred the disfavor of the Holy Roman emperor Frederick Barbarossa, a Waiblingen, in 1180, his lands were forfeited to a duke of the Wittelsbach family, a dynasty that was to dominate Bavarian history until the end of World War I.).

Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy

It was during the reign of the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (1152–90) that the terms Guelf and Ghibelline acquired significance in Italy, as that emperor tried to reassert imperial authority over northern Italy by force of arms. Frederick’s military expeditions were opposed not only by the Lombard and Tuscan communes, who wished to preserve their autonomy within the empire, but also by the newly elected (1159) pope Alexander III. Frederick’s attempts to gain control over Italy thus split the peninsula between those who sought to enhance their powers and prerogatives by siding with the emperor and those (including the popes) who opposed any imperial interference.

Frederick’s supporters became known as Ghibellines, while the Lombard League (the medieval alliance formed in 1167 and supported by the pope) and its allies became known as Guelphs. After being defeated in the Battle of Legnano in 1176, Frederick recognized the full autonomy of the cities of the Lombard League.

During the following struggles between the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II (who reigned between 1220–50), nephew of Frederick Barbarossa, and the popes, the Italian parties took on their characteristic names of Guelph and Ghibelline (beginning in Florence) and contributed to intensifying antagonisms within and among the Italian cities.

We have to remember that Frederick II was King of Sicily (1198–1250), as well as King of Germany from 1212 and then Holy Roman Emperor. The title of Holy Roman Emperor was held in conjunction with the rule of Germany and northern Italy.

Both Frederick II and the Pope wanted universal power.

The Guelphs sided with the Church, while the Ghibellines sided with the Empire.

Guelphs tended to come from wealthy mercantile families, whereas Ghibellines were predominantly those whose wealth was based on agricultural estates.

Guelph cities tended to be in areas where the Emperor was more of a threat to local interests than the Pope, and Ghibelline cities tended to be in areas where the enlargement of the Papal States was the more immediate threat.

The struggle between these two forces gave rise to a series of conflicts and alliances among Italian cities, since some sided with the emperor and others with the Pope.

The same city often changed sides, depending on who took power. Members of the opposing faction were also often exiled after a revolution of power, just like Dante. In fact this rivalry was especially ferocious in Florence, where the Guelfs were exiled twice (1248 and 1260) before the invading Charles of Anjou ended Ghibelline domination in 1266.

Sometimes, there could also be different Guelf and Ghibelline factions in the same city.

For example, in Florence after the fall of the Ghibellines, the Guelphs divided into the White Guelphs and Black Guelphs. Dante belonged to the White Guelphs.

In general, the Guelphs were more often victorious. Also, in 1266, the Capetian House of Anjou, which belonged to the Guelph party, took the crown of Sicily.

In any case, Guelph and Ghibelline membership quickly changed from its original meaning and in each city often pointed to a choice according to specific economic interests.

In the middle of the fourteenth century, the jurist Bartolo da Sassoferrato wrote an essay on this issue and said that the two labels were no longer linked to the pope and the emperor so that even an opponent of the Church could define himself as a Guelph and vice versa.

Also, the same person could define himself as a Guelph in one place and as a Ghibelline in another.

In heraldry

The original religious and ideart ological clash still gave the fight between the two factions an iconography (see the imperial eagle on one side and Christian symbols on the other), as well as a sort of mythology from which propaganda could draw.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, armies of the Ghibelline communes usually adopted the war banner of the Holy Roman Empire—a white cross on a red field—as their own.

Guelph armies normally reversed the colors—a red cross on white.

These two schemes are prevalent in the civic heraldry of northern Italian towns and remain a revealing indicator of their past factional leanings.

Traditionally, Ghibelline towns like Pavia, Novara, Como, Treviso, and Asti continued to sport the Ghibelline cross. The Guelph cross can be found on the civic arms of traditionally Guelph towns like Milan, Vercelli, Alessandria, Padua, Reggio, and Bologna.

Some individuals and families indicated their faction affiliation in their coats of arms by including an appropriate heraldic “chief” (a horizontal band at the top of the shield).

uelphs had a capo d’Angio or “chief of Anjou” containing yellow fleurs-de-lys on a blue field, with a red heraldic “label,” while Ghibellines had a capo dell’impero or “chief of the empire” with a form of the black German imperial eagle on a golden background.

Families also distinguished their factional allegiance by the architecture of their palaces, towers, and fortresses. Ghibelline structures had “swallow-tailed” crenellations, while those of the Guelphs were square.

This post was originally published in July 8, 2013, and has been updated and enriched on April 19, 2017

Picture by Wikimedia

As a myth, its source could be unidentifiable. However, its basis is merely an illusion in the eyes of the author. Wherein, the repercussions could be, collectively, a horrendous malaise. Upon which, the truth of the matter supercedes the presence of that malaise. How long would it take to have a story like this published??